“Life was quiet and simple then, and a circus or carnival coming to town were really big events. Daddy always took off from work, and they would take us to the afternoon performance of the circus, which was always held in a huge tent. Bama would always go too. We would go to bed early when the circus was coming so that we could get up around four in the morning to go down to the Y&MV Railroad Depot to watch them unload. It was so exciting seeing the animals being unloaded, and then we would ride out to see the laborers, or roustabouts as they were called, putting up the huge tent. About eleven o’clock there would be a parade in downtown Greenwood with all of the horses and pretty girls and the calliope, which played music, and the clowns and cowboys. School would be let out for circus day.

“We would go into the sideshow first where they had ‘freaks’ of all kinds. There would be a fat lady, a rubber man, midgets, a sword swallower, a man who ate fire, etc. You had to pay extra to see them. After the main performance you could pay some more and stay for the Wild West Show. We took it all in, and then on the way out poor Daddy had to buy souvenirs for all of us. There were birds made of paper on sticks which looked like they were flying when you twirled them around, and dolls dressed in pink and blue feathers, and always there were Cracker Jacks, which we didn’t even like but always had to have because of the prize inside.

“The circuses and carnivals usually came in the fall because that was cotton picking season, and there was more money circulating then. At that time Greenwood depended on farmers for the town’s economy. All of the cotton was picked by hand, and that was the only time of year that the Negroes, who were sharecroppers, had any money. They lived in little shacks on the plantations and received a small share of the money when the cotton was sold. Cotton was the only crop grown in the Delta then, and Mama and Daddy would get excited every year when the oil mill began operating for another season. Years later when she would hear an oil mill whistle blow, Mama would say ‘That makes me so lonesome.’ She would be remembering those happy years when she and Daddy were young and he was managing the Buckeye Mill.

“There was a cotton field right down the street from us, and one time Mama made each of us a long cotton sack out of fabric and let us go with Rawa and Buddy and their friend John Howard Freeman to pick cotton for Mr. Hardin, who had planted it. I was too small to do much picking, but I did find a baby watermelon, and that made my day worthwhile. It was about the size of an orange and, of course, not fit to eat. At the end of the day, Mr. Hardin, who was the father of Olympic track star Slats Hardin, weighed the cotton and paid us for it just like he did with the Negro pickers.“Poor white families also made money picking cotton. It was hard work, and you would see fields of the white cotton with hundreds of pickers pulling their sacks over their shoulders and filling them with cotton. They would sing and talk and laugh while they picked.”She loved a spectacle.

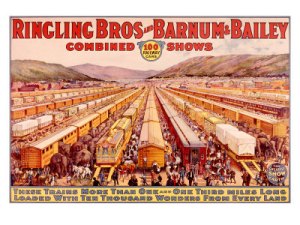

As I’ve mentioned in previous blogs, Sara would anticipate the arrival of the circus trains (or, later, the trucks) as eagerly at 40 as she did at 4. When the huge colorful posters went up downtown, announcing the imminent arrival of Ringling Brothers or somesuch, she would pull us over to soak in every detail, and by circus day it was as if the Queen of England and her court were headed for the Delta. Sara would bustle into our bedroom in the predawn dark, urging us in and out of the bathroom and into our clothes. I can still feel the dew around my Keds as we stood in a field out near Greenwood High School, sun barely over the horizon, the stink of animal dung hanging thick in the air, watching those elephants marching away from the tent center with ropes attached to their collars. It was an amazing sight to see that canvas rising from the dirt, the Big Top taking shape right in front of our sleepy eyes. Sara would scoot around with her flip-top steno pad, cornering a roustabout or ringmaster for a quick interview. Then it was back home to wait for the real show, and we never left without geegaws and souvenirs, which always thrilled her more than us.

It just couldn’t have possibly have been so rosy a world as Sara described. Greenwood and the Mississippi Delta, in the 1920s, was a harsh and brutal place for many of its inhabitants, white and black, but the Evans girls were so nurtured and adored in their brick bungalow family that all of that faded away. For Sara, looking back from 1990 to her childhood, Greenwood was a magical town, set squarely in the center of the universe, and peopled by kind and quirky characters whose lives were enriched by the arrival of circuses, showboats and carnivals.

Of course, there wasn’t a circus very often in Greenwood. But there were parades, and I don’t believe we ever missed one. Besides the thrill of Band Festival (a story for another day), there were patriotic parades and welcome-home parades and the apex, the ultimate: Friday afternoons when Greenwood High School’s band took over Howard Street, complete with cheerleaders, floats and pep rallies on Barrett’s corner. Sara was a Bulldog to the core and loved the tradition and hometown hoopla of those days.

She took Cathy and me out on a few cottonpicking expeditions, probably just so we could say we’d done it, or maybe in search of another baby watermelon.

No comments:

Post a Comment